Tularemia

What is Tularemia?

Tularemia is a serious, highly infectious and potentially deadly disease of animals and humans caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis. In 1994, it was removed from the notifiable list of diseases because of the low number of human cases. However, tularemia has recently re-emerged as a threat in the US and elsewhere. Rabbits, hares, and rodents are especially susceptible and often die in large numbers during outbreaks. The microbe has been found in over 300 species of mammals, birds, amphibians, arthropods, and even fish, and the disease occurs worldwide though most commonly throughout North American and Eurasia.

Humans can become infected through several routes including tick, deer fly and mosquito bites, skin contact with infected animals, water or soil, ingestion of contaminated water, inhalation of contaminated aerosols or soil dust, and laboratory exposure as it is highly infectious when grow in culture. F. tularensis has been classified as a Category A select agent because of its potential as a biological weapon. F. tularensis can survive for weeks outside of a living host.

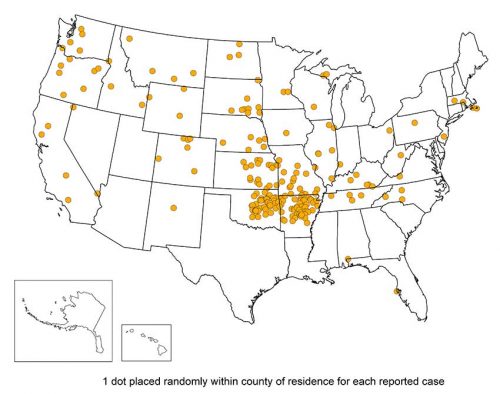

Tick-borne infections of tularemia in humans and dogs are known to be transmitted by the American Dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), the Rocky Mountain Wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni), and the Lone Star tick (Amblyomma americanum). Infections due to tick and insect bites usually take the form of ulceroglandular or glandular tularemia. Tularemia occurs throughout the U.S. and has been reported from all states except Hawaii. It is most prevalent in the western and south-central parts of the country, but also occurs in areas of the Pacific Northwest, and parts of Massachusetts, including Martha’s Vineyard.

Hunters are at particular risk, as exposure to tick habitat is higher, as well as handling of potentially infected animals such as rabbits, muskrats, prairie dogs and other rodents.

Hunters are at particular risk, as exposure to tick habitat is higher, as well as handling of potentially infected animals such as rabbits, muskrats, prairie dogs and other rodents.

Anglers also may have increased exposure by fishing in tick habitats and through contact with contaminated water. Precautions such as wearing gloves should be taken when handling sick or dead wildlife. Infection due to handling animals can result in glandular, ulceroglandular and oculoglandular tularemia.

Oropharyngeal tularemia can result from eating under-cooked meat of infected animals, most often rabbit.

Many other animals have also been known to become ill with tularemia. Domestic cats and dogs have been known to transmit the bacteria to humans. Veterinarians and other animal care workers are at higher risk of infection. Avoidance of or taking precautionary measures when handling sick or dead animals is important in prevention of this disease.

Is Tularemia in Colorado?

Is Tularemia in Colorado?

Tularemia is a reportable disease in Colorado. Among the 26 counties that reported human cases between 2012 and 2017, Boulder, Larimer and Weld counties were three of the highest reporting counties. According to the Colorado Department of Health and Environment, 2015 was year 2 of a three year epidemic, and 52 people in Colorado were diagnosed as having a clinical illness from infection with F. tularensis, though very few cases were tracked to a tick bite. These cases presented with a diverse range of symptoms including glandular/ulceroglandular, pneumonic, gastrointestinal, and typhoidal. Also in 2015, 37 animals tested positive for tularemia in Colorado. Twenty-three of these animals were rabbits and 10 were rodents. A total of 62 dogs and cats were tested for tularemia; two cats and two dogs were positive”. Counties testing for wildlife and pets between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2017 reported only 10 positive cases, primarily in wildlife.

Animal species reported as testing positive in Colorado include many rodents; tree squirrel, prairie dog and beaver with highest incidence, as well as other wildlife; coyote, rabbit and fox having the highest case numbers. Infected birds, as well as domestic cats and dogs have also been reported in Colorado. Like humans, wildlife and domestic animals may be infected through the bite of an infected tick, deer fly or mosquito, or may acquire through direct contact with a dead animal or contaminated air, water or soil source.

What are Tularemia Symptoms?

Symptoms of tularemia usually develop within three or four days of inoculation, though in some cases it can take up to 10 days for the disease to manifest. The signs and symptoms of tularemia are variable depending on how the bacteria enter the body. Symptoms and illness range from mild to life-threatening. Meningitis is an uncommon but potentially serious complication of tularemia infection. All forms of tularemia include fever, which can be as high as 104 °F. The main forms of tularemia are listed below:

- Ulceroglandular is the most common form of tularemia and usually occurs following the bite of a tick, deer fly or mosquito; or after handling an infected animal. A skin ulcer will appear at the site where the bacteria entered the body. Swelling of lymph glands, usually in the armpit or groin occur. High fever, chills, swollen glands, headache and extreme fatigue.

- Typhoidal, sometimes called septicemic tularemia, is the next most common, and most serious form. Fever, exhaustion and weight loss as well as vomiting, abdominal pain and rash may occur. Lungs may become involved and pneumonia is a common feature of this infection. It is probably acquired by ingestion, although the precise mode of transmission is not completely clear.

- Pneumonic results from breathing dusts or aerosols containing the organism. It can also occur when other forms of tularemia are untreated and the bacteria spreads through the bloodstream to the lungs. Symptoms include a dry cough, chest pain, and difficulty breathing. Glandular is typically acquired through the bite of an infected tick, deer fly or mosquito; or from handing infected animals. This form lacks the development of an ulcer as in the ulceroglandular form. It is also acquired through the skin, and may not require a scratch or abrasion.

- Oculoglandular occurs when the bacteria enter through the eye. A person may become infected while field dressing or butchering an infected animal from a splash of blood or when the eyes are rubbed after handling an infected animal. Symptoms include redness, irritation and inflammation of the eye (conjunctivitis) and swelling of lymph glands in front of the ear.

- Oropharyngeal results from consuming contaminated food or water. Common symptoms include sore throat, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Mouth ulcers, tonsillitis, and swelling of lymph glands in the neck may occur. Abdominal pain and intestinal ulcerations are common.

How is Tularemia Diagnosed?

Tularemia can be difficult to diagnose and is diagnosed based on signs and symptoms as described above. It is a rare disease, and the symptoms can be mistaken for other, more common, illnesses. Information regarding likely exposures, such as tick and deer fly bites, contact with sick or dead animals or potentially contaminated air, water or soil sources should be considered. The presence of the characteristic ulcer is suspicious for the disease.

How do you test for Tularemia?

Blood tests and cultures can help confirm the diagnosis. Approximately half of all patients will exhibit non-specific abnormalities in liver function and some patients develop elevated creatine kinase levels, however standard blood tests are not specific.

A number of specific tests exist for tularemia, but they are not widely available and antibodies don’t typically present in the first ten days after exposure.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests can also be utilized.

- F. tularensis can be grown in culture. Test samples should come from sputum or pharyngeal washings, as the bacteria is not present in large numbers in blood. Laboratory personnel are advised to take strong precautions as workers can themselves become infected. Test samples should come from sputum or pharyngeal washings, as the bacteria is not present in large numbers in blood.

How is Tularemia Treated?

Antibiotics used to treat tularemia include streptomycin, gentamicin, doxycycline, and ciprofloxacin. Treatment usually lasts 10 to 21 days depending on the stage of illness and the medication used. Although symptoms may last for several weeks, most patients completely recover.

Additional Resources:

Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) webpage and personal communication with former CDPHE Epidemiologist, Leah Colton

Columbia University Medical Center-Lyme and Other Tick-borne Diseases Research Center

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

USGS National Wildlife Heath Center

LDA/Columbia 17th Annual Conference material, presented by Dr. Timothy Lepore, 2016